Spenser’s Cantos of Mutability (Week 2): Where Change Reigns — and Where It Ends

- Ken Kalis

- 22 hours ago

- 4 min read

Last week, we stood at the threshold of Edmund Spenser’s Cantos of Mutability, where the great poet turns from the virtues he has spent a lifetime shaping — holiness, justice, courtesy — and asks a deeper, more unsettling question.

What happens to virtue, to order, even to goodness itself, in a world where everything changes?

This week, before we go any further, it helps to know exactly where we are — and where Spenser is taking us.

Spenser's Plan

The Cantos of Mutability consist of two complete cantos, followed by a fragmentary conclusion — two unfinished stanzas that close The Faerie Queene itself.

These cantos come at the very end of Spenser’s life’s work, and they read like a final meditation rather than another episode of knightly adventure. Here, Spenser is no longer forming a single virtue; he is weighing the whole world.

Last week, we entered Canto I, where Mutability steps forward to make her case. She does not speak wildly or foolishly. She speaks with evidence.

Everything beneath the heavens, she argues, is subject to time: the seasons turn, kingdoms rise and fall, bodies age, customs fade. Nothing we see remains fixed.

Courtesy may restrain the tongue, justice may order society, holiness may shape the soul — but all of them must be practiced again and again because they live under pressure. Change is not the exception; it is the rule.

This week, we move deeper into Canto I, allowing Mutability’s argument to unfold without interruption. Spenser does not rush to answer her.

Instead, he lets her claim settle in, forcing us to acknowledge how complete her rule appears to be. If we judge by experience alone, Mutability seems to govern all things. Time presses in on every side, and nothing created escapes its reach.

It is here that Spenser introduces a quiet but decisive tension. He recalls a promise beyond the present age:

“Then gin I think on that which Nature sayd,/Of that same time when no more change shall be.”

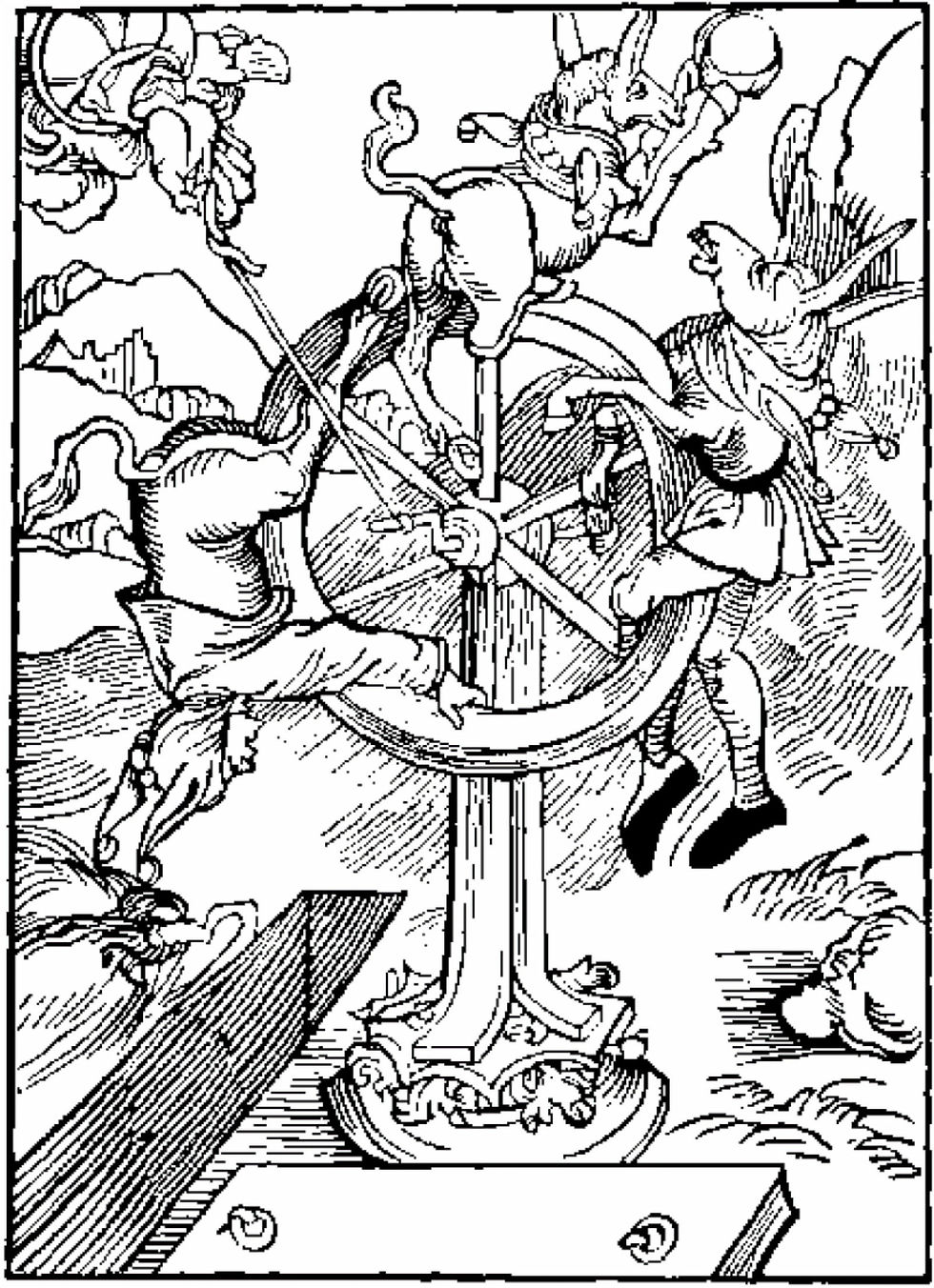

The line does not deny the power of change. It places it within a larger story. Time reigns now — but not forever. Mutability may rule the order of nature, but she does not rule its end. Here is the One who does:

Where We Are Going

Over the coming weeks, we will move slowly and deliberately through these cantos.

Weeks 1–2 (Canto I): Mutability’s argument — the reign of change in the created world.

Weeks 3–4 (Canto II): The great trial scene, where Nature herself presides, and the limits of time are revealed.

Final Week: Spenser’s unfinished conclusion — a deliberate stopping point that gestures beyond poetry, beyond history, toward eternal rest.

Spenser’s purpose is not despair, nor escape from the world. It is clarity.

He teaches us how to live faithfully in a changing world without mistaking change for what is ultimate.

Virtue matters.

Order matters.

Holiness matters.

But none of them can bear the full weight of our hope.

That hope rests elsewhere — beyond the turning of seasons, beyond the rise and fall of kings, beyond the long labor of time itself. The Cantos of Mutability do not end with chaos, but with anticipation: a looking forward to that promised moment when change itself will be brought to rest.

For now, Spenser asks us to stay with the question, to resist easy answers, and to learn how to live well under time — while fixing our hearts on the One who stands beyond it.

******************************

Abide With Me!

Abide with me; fast falls the eventide;

The darkness deepens; Lord with me abide.

When other helpers fail and comforts flee,

Help of the helpless, O abide with me.

Swift to its close ebbs out life’s little day;

Earth’s joys grow dim; its glories pass away;

Change and decay in all around I see;

O Thou who changest not, abide with me.

Not a brief glance I beg, a passing word;

But as Thou dwell’st with Thy disciples, Lord,

Familiar, condescending, patient, free.

Come not to sojourn, but abide with me.

Come not in terrors, as the King of kings,

But kind and good, with healing in Thy wings,

Tears for all woes, a heart for every plea—

Come, Friend of sinners, and thus bide with me.

Thou on my head in early youth didst smile;

And, though rebellious and perverse meanwhile,

Thou hast not left me, oft as I left Thee,

On to the close, O Lord, abide with me.

I need Thy presence every passing hour.

What but Thy grace can foil the tempter’s power?

Who, like Thyself, my guide and stay can be?

Through cloud and sunshine, Lord, abide with me.

I fear no foe, with Thee at hand to bless;

Ills have no weight, and tears no bitterness.

Where is death’s sting? Where, grave, thy victory?

I triumph still, if Thou abide with me.

Hold Thou Thy cross before my closing eyes;

Shine through the gloom and point me to the skies.

Heaven’s morning breaks, and earth’s vain shadows flee;

In life, in death, O Lord, abide with me.

Hen¬ry F. Lyte, 1847.

Comments